It’s not always apparent what happens behind the scenes when you hit “search” on any service, but we’re gonna see how the sausage is made. One of +yaw’s core objectives has been to be as quick as possible. In the context of a user, they could be at home on WiFi or in the middle of camping on an EDGE cellular connection. With this in mind, it’s important to deliver results as quickly as possible. There’s a lot to optimization that I won’t touch on in this post, but a significant portion is improving database performance.

what is “database performance?”

Whenever a road search happens on PositiveYaw, a query on the database must be performed. The database itself–as of November 2019–holds over 8 million roads. Of the 8 million or so, about 3.5 million roads are considered ‘good enough’ to be rated with a YawRate. If you’re familiar with +yaw you’ll know how a YawRate works: it’s an objective rating of a road’s features.

Given a GPS point and search radius for a user’s query, +yaw needs find a list of roads that match, sort them, and have all the details of the road. How can this be done in the shortest amount of time?

constraints

There’s only so much that can be done on inexpensive hardware/hosting providers, and open source software. PositiveYaw is built on Python, PHP, JavaScript, and MySQL. The biggest constraint on delivering results quickly is MySQL, and the fact that +yaw is built on a shared server that hosts many other websites. This means that raw performance is not exactly the server’s forte. Quickly scanning 3.5+ million road segments within a GPS point’s radius and the best YawRates is mostly down to SQL optimization. Let’s check out the biggest opportunities and run some experiments.

understanding slowness

Performance improvement for the sake of improving number is not worth anything unless you are sure it is where the majority of time is spent–or it is low-hanging fruit for improvement. Improving performance by 10 seconds is the wrong thing to do if there is a task that saves 10 minutes–assuming they both requires the same amount of effort. Performance improvement divided by effort.

In PositiveYaw’s specific case, it didn’t appear that all road searches took the same amount of time–it was clear that searches with many results took less time than searches in areas where there weren’t as many relevant roads. In this case, I wanted to understand why, and if it could feasibly be solved with the above constraints in mind.

hypothesis

In the current version, the database is queried and returns a list of roads and their respective details. The query sometimes fails, or takes a very long time. I suspect that there is some reason why the initial index used to cover the GPS coordinates and YawRate worked well when being tested, but not in production. It is unclear what makes it fail / timeout, and it is hard to understand why an area with no results takes a such a long time to fail and/or give zero results.

I decided to benchmark the current version, then create the first test for returning road unique IDs only. After, I’ll create a second test which returns road unique IDs and then queries the details for each respective road.

The initial hypothesis: there is something that causes a significant slowdown when returning all details within one query. The current version does this, but it unclear why. If the index on the query is not correct, then a test returning road unique IDs alone should be just as slow.

the experiment structure

A repeatable experiment was needed to understand why some searches took longer than others, and why some timed out. It was hard to comprehend–or at least accept–because database performance was previously a huge point of research and development. Let’s review how the experiment was structured.

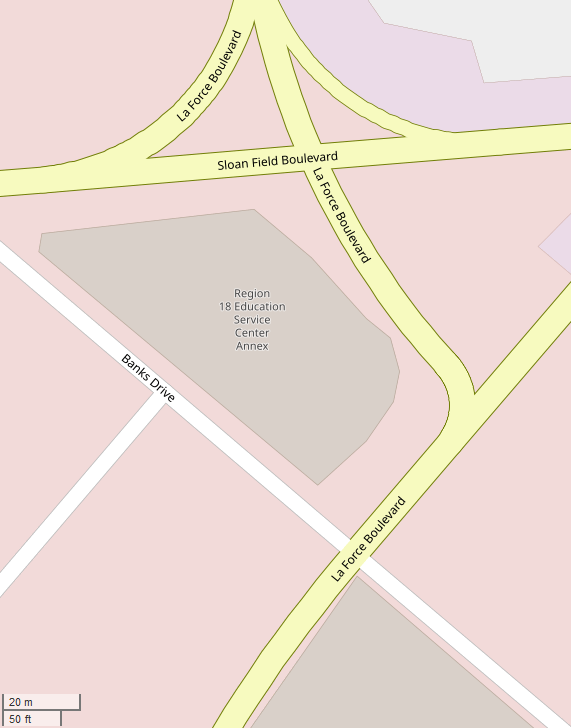

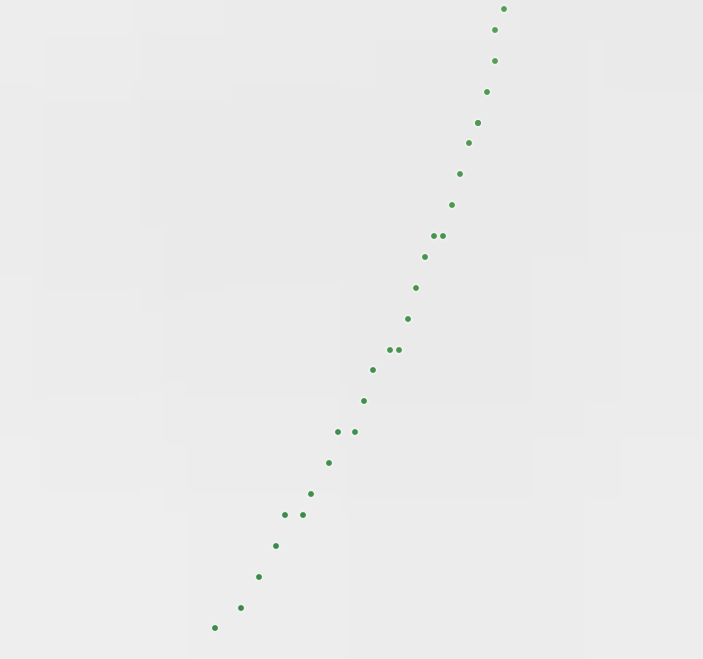

First, the experiment needed to be random, but repeatable. It didn’t make sense to actually pick a list of GPS points and manually search them. In this case, we’ll use a program to generate random latitude and longitude points. This will allow a random seed to be used and create repeatable GPS points to be searched.

Second, it needed to be able to be timed. We’ll use some simple timers to measure time taken to get a result.

Third, we need to know if something failed by timing out. We’ll note an error code each time a result is given(or not!) to measure failure rate.

You’ll notice above that we’ve already gathered requirements for the experiment. You can see the code in the next segment.

the ugly code

Perfection is the enemy of the good. Here we’re only testing assumptions and attempting to get a quick answer to potentially dig deeper. Check out this quick python code I wrote to generate GPS coordinates and time the result:

# Just a simple script to test speed of mysql query structure.

import requests

import random

import time

# functions to randomize GPS points approximately within

# the USA (current scope of the +yaw database)

def generate_lat():

lat = random.uniform(32, 49)

lat = round(lat, 5)

return str(lat)

def generate_lng():

lng = random.uniform(-120, -78)

lng = round(lng, 5)

return str(lng)

def run_test(numruns = 100):

random.seed(444)

urlbase = 'https://api.positiveyaw.com/redacted'

for x in range(0, numruns):

full_url = urlbase + 'lat=' + generate_lat() + '&lng=' + generate_lng()

r = requests.get(full_url)

print(str(x) + ": " + str(r.status_code))

numruns = 100

start = time.time()

run_test(numruns)

end = time.time()

print("")

print("EXECUTION TIME:")

time_elapsed = end-start

print(str(time_elapsed))

print("Average time per call: " + str(time_elapsed/numruns))running the experiment

Running the experiment was far from scientific–but being quick and dirty is good enough to understand the short comings of the current search scheme.

There were a few things considered when running the tests:

- Caching didn’t seem to exist or have an effect on speed.

- Network and CPU load of the computer executing the script were ignored as they appeared to have a negligible effect on the results.

database index design

Gonna get nerdy (nerdier) here for a bit–the MySQL database table has a few indexes on it, one that was designed specifically for this particular function: searching by GPS point and YawRate. The intent was to create a quick lookup despite having millions of roads around the world to evaluate. When designing the query, it was strategic that the query itself fell into this index, otherwise it would be useless. If you are looking to optimize MySQL, I suggest you check out this talk on YouTube by Dr. Aris Zakinthinos. It has been the best resource I have seen to understand MySQL’s EXPLAIN statement without going too deep into code, but clarifying why and how things are handled the way they are.

After spending so much time during the design phase, it made little sense as to why some queries took a very long time, and some were as quick as expected. I wanted to dig deeper, since I was wary to remove data from the database or re-design the schema.

modifying the SQL query

Without exposing the entire schema of the database, the different versions of the queries were as follows:

- Current version: Search on GPS point, sort by YawRate, and return the top results with all relevant details. Essentially,

SELECT * FROM roads WHERE lat BETWEEN num1, num2 AND lng BETWEEN num3, num4 ORDER BY yawrate LIMIT 10 - Test version 1:

SELECT road_id FROM roads WHERE lat BETWEEN num1, num2 AND lng BETWEEN num3, num4 ORDER BY yawrate LIMIT 10 - Test version 2 (two queries!):

SELECT road_id FROM roadsWHERE lat BETWEEN num1, num2 AND lng BETWEEN num3, num4 ORDER BY yawrate LIMIT 10[process results to search on road_id(s)]SELECT * FROM roads WHERE road_id = 1

the data

Perhaps more rigorous testing should be done, but this was enough for me to be satisfied with the result, and have a course of action. Here are the results from each test:

| Benchmark | Test 1 | Test 2 | |

| Average Time | 10.97 | 1.34 | 1.76 |

| Standard Dev. | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Average Fail Rate | 6% | 0% | 0% |

Each test was run 5 times. All time listed in seconds. Failure rate determined by percentage of 500 status codes in the 100 calls made during each test.

course of action

When originally testing the SQL query, the EXPLAIN result showed that the index was working as intended, and it would be at peak performance. My mistake came after optimizing the SQL query and database. It became clear that somehow the index actually didn’t cover a SELECT query that covered columns outside of the WHERE and ORDER BY clauses. It didn’t quite make sense to me, since lat, lng, and yawrate were covered by the index. Surely, selecting additional columns wouldn’t have an effect on performance, right? Incorrect.

I struggled to find a reason why this was the case, but I found a post by Jon Galloway at Microsoft that appears to describe the issue: index coverage. It’s not MySQL, but I’m going to assume a similar concept applies. I don’t know enough about databases to truly say either way!

There’s likely more ways to solve the problem, but after running test 2 I was more than satisfied with the result. I have decided to implement it (at least for now) without touching the database schema or data.

As always, feedback is welcome! I’m not an expert, so I’d love to hear from you. Please feel free to email me: jackson@positiveyaw.com

At the time of writing, PositiveYaw indexes over 8 million road segments, comprised of 155 million GPS points. If you’d like to checkout roads near you, search our database of roads at https://app.positiveyaw.com

PositiveYaw is free because of you.

Sifting through data takes a long time, and PositiveYaw is a result of years of dealing with small issues like this. We hope you enjoy the work we’ve done enough to support us.

Keep it mellow, don’t cross yellows.

-Jackson